The ongoing negotiations to establish an international legally binding instrument (LBI) or treaty to regulate corporate power have reached a critical juncture 10 years since their inception. As the process unfolds, the encroachment of corporate influence on both State decision-making and the text of the draft treaty threatens to undermine its core principles. Corporate capture of governance at both the international and national levels lead to the prioritisation of profit over environmental and people’s rights, causing systemic injustices that perpetuate poverty, inequality, environmental degradation, and violence in various forms – including, at its most severe, genocide.

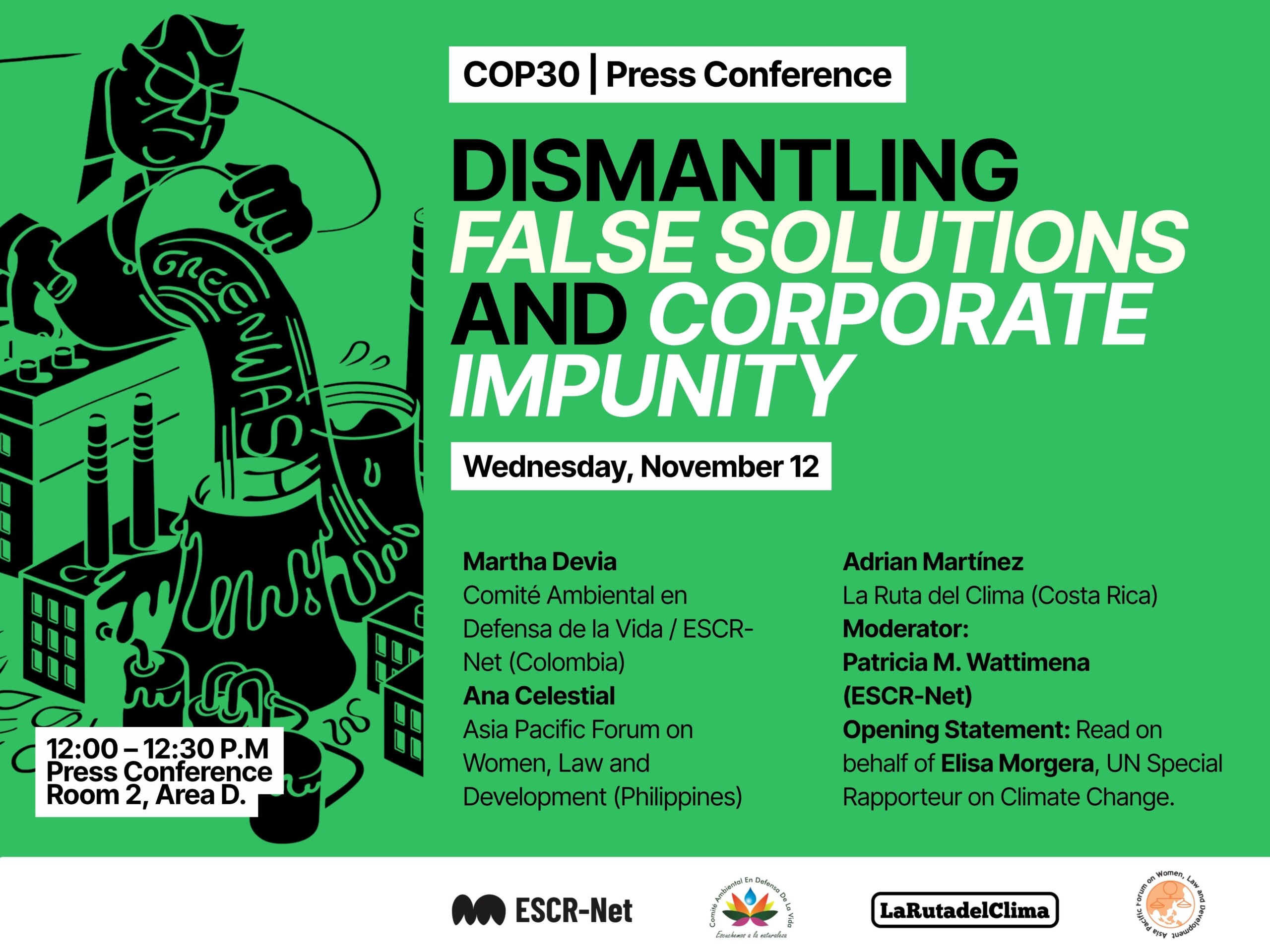

Three major business representatives were present in the negotiating space during the 10th session of the negotiations, which took place in December 2024: the United States Council for International Business (USCIB), the International Organisation of Employers (IOE) and the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). Several statements by these representatives very blatantly called for the weakening of the LBI text – particularly in relation to calls by social movements and other civil society organisations to strengthen corporate legal liability and facilitate the enactment of extraterritorial obligations and access for victims of corporate violations and abuses to justice across a number of jurisdictions.

For instance, corporate actors in the room threatened withdrawal of investment from State parties if strong provisions are not removed from the text. Specifically, USCIB stated that the current draft LBI encourages a cut-and-run approach that would result in market exits and cause economic, trade and job losses for developing countries. In the same statement, USCIB argued against establishing liabilities for natural persons so as to shield corporate managers from accountability. This is entirely unsurprising. Corporate actors can be expected to prioritise their survival and profit margins over the ultimate guarantee of corporate accountability and the protection of human rights. For this reason, members of ESCR-Net – the International Network for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights – have consistently called for the treaty negotiations to become completely free from corporate influence.

Corporate actors must not be permitted to play a role in shaping decisions about their own accountability, as it is unacceptable for the perpetrator or potential perpetrator of a rights violation or environmental harm to have a say in determining the rules governing their own liability. The very notion of allowing corporations to influence the terms of their own liability is fundamentally flawed. This constitutes a clear conflict of interest as corporations are driven by profit motives that inherently clash with the protection of human rights and environmental standards. It violates basic principles of fairness and due process, undermining the possibility of establishing effective and fair mechanisms of redress. Additionally, in any serious normative framework, the party that has caused harm cannot participate in defining the limits of its own liability, as this would be tantamount to legitimising impunity under the guise of consensus.

Despite this, the aforementioned corporate lobbyists represent some of the worst corporate actors of our time. It is unreasonable to expect such corporate representatives to truly and voluntarily hold themselves or their clients accountable for the harm they may inflict via a non-adjudicative body, nor should they be allowed to determine the scope of their own responsibilities. Such a setup would be a direct contradiction to justice and accountability.

Take the case of Indigenous Peoples, who continue to face multiple challenges and threats including a lack of self-determination, biodiversity losses, climate injustice, deforestation, land degradation, commercialisation, land-use change, land grabbing, criminalisation, militarisation and other human rights violations. Under the guise of ‘conservation’ or ‘energy transition’ projects, corporate entities operate on Indigenous territories with impunity and violate Indigenous Peoples’ rights without obtaining their free, prior and informed consent (FPIC). Massive displacement of Indigenous Peoples, loss of livelihood, and the erosion of their culture and identity are just some of the harmful effects that occur as a result of these projects.

In many instances, Indigenous Peoples are not even privy to basic information about projects in their territories. While Indigenous leaders have called, through the treaty process, for victims of corporate abuses or violations to have the right to access information, corporate representatives work openly to undermine it. A statement from IOE at the 10th negotiating session last year clearly intended to limit access to information. This is why we need international regulation to hold corporate actors accountable and that is free from the influence of corporations.

While the LBI process remains influenced to an extent by corporate actors, we still have an opportunity to change it and we must change it. Learning from the World Health Organization (WHO)’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), we need to guard against corporate capture in policymaking and this can be regulated. Article 5.3 of the FCTC requires all Parties, when setting and implementing their public health policies with respect to tobacco control, to ‘act to protect these policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry’. This means that the FCTC process explicitly recognised the conflict of interest between the tobacco industry and public health, and it took steps to protect policymaking processes from industry interference. The FCTC serves as a model for how we can safeguard the treaty negotiations and any national decision-making processes on public services from corporate influence, ensuring that the public interest prevails over corporate agendas. We must insist that this be further expanded and more explicitly incorporated throughout the text of the treaty so it may fulfil its intended mission.

Corporate capture of international governance is happening at alarming rates and corporate interests are increasingly dictating the terms of global policymaking. This has been particularly evident in the context of the United Nations (UN) and other multilateral forums, where corporations have gained privileged access to decision-making spaces. The corporate capture of national governance – especially in the Global North – has further exacerbated this issue, as these governments have tended to prioritise corporate interests over public welfare, often obstructing efforts to establish a robust legal framework for corporate accountability.

In the face of this growing corporate power, we must ask: are States willing to allow public decision-making to be swayed by corporate interests rather than the will of the people they are meant to represent? Are we willing to accept a world where the economic elite – representing just 1% of the global population – shapes decisions that affect the lives and rights of the other 99%? The answer must be a resounding no. It is essential that States, particularly those in the Global South, continue to lead efforts to free the treaty process from corporate interference, and push for an LBI that curtails corporate power and holds corporations accountable for the harm they cause. We cannot afford to allow corporate influence to dictate the terms of this treaty, as doing so would risk perpetuating the very corporate impunity that this process seeks to address.

The assault by corporate power on the international human rights and environmental agenda is today more evident than ever,taking the form of attacks on global governance and multilateral institutions. The need for action is urgent. To this end, ESCR-Net has put forward several key red lines that must not be crossed as we elaborate a final draft of the treaty text.7

Corporate capture of international governance is directly undermining our efforts to set internationally binding laws to protect human rights, the environment and the common good. The time has come for States to demonstrate leadership in halting this obstruction, and for the international community to commit to a world where human rights are placed above profit and where corporations are held accountable for the harms they inflict. Change must also happen across the UN system – starting from the Office of the Secretary-General, who has introduced concerning initiatives over the years calling for ‘multistakeholderism’ and dialogue between ‘stakeholders’ but ultimately inviting corporate actors and economic elites to be part of UN decision-making spaces.

The LBI represents an opportunity to help direct us towards a more just and equitable world, one in which the rights of individuals and communities are protected from corporate power. But to realise this vision, we must ensure that corporate influence is eliminated from the negotiating process and the outcome. The LBI must be firmly rooted in the principles of justice, human rights and environmental sustainability, with an unwavering commitment to protecting the public interest. The future of global governance depends on it.