Research focus

The research examined:

- The climate crisis, adaptation, and mitigation strategies

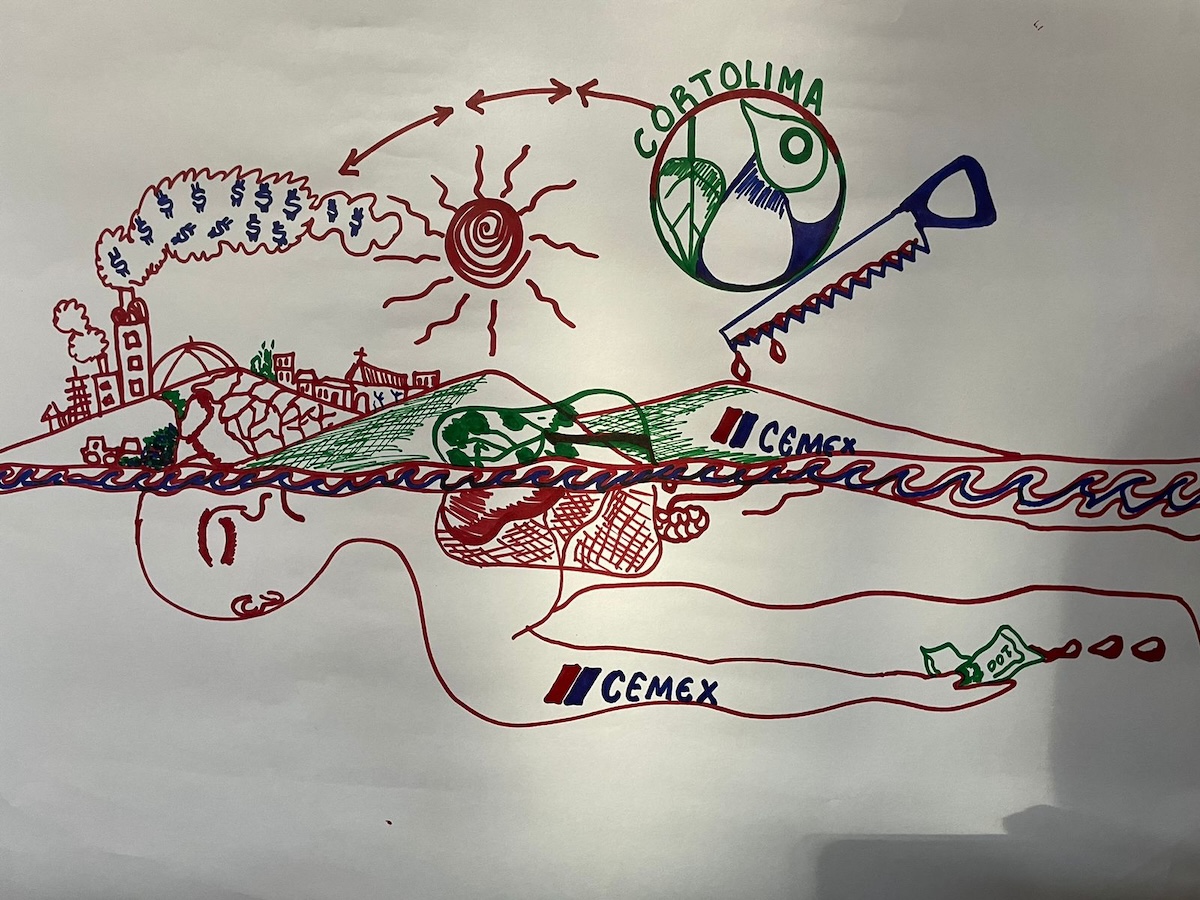

- Extractivism and human rights

- Environmental, cultural, and spiritual losses from climate change and extractive projects

- Impacts on water sources, biodiversity, and food sovereignty

- Community resilience practices such as agroecology, seed protection, rainwater harvesting, ancestral medicine, and environmental education

These topics were chosen because they reflect the interconnected realities of local communities, where climate change is inseparable from cultural identity and political struggle.

Key findings

- Loss of forests and páramos

Accelerated deforestation and forest fires—driven by drought, uncontrolled burns, and rising temperatures—are destroying ecosystems vital for water regulation and climate balance. With them go native species, animal routes, and traditional knowledge. - “Cornering” of species

Communities observe how plants and animals, before disappearing, move into shrinking, hostile habitats. Without food or shelter, many collapse in their life cycles—a silent warning of local extinctions. - Water depletion and contamination

Streams, springs, and rivers like the Saldaña are reduced by drought and overuse from mining and other extractive activities, while industrial waste and deforestation contaminate recharge areas. Some communities now walk long distances for clean water, relying on rainwater cisterns as a resilience measure. - Decline in biodiversity and pollinators

The loss of bees, butterflies, and birds threatens crop pollination and ecosystem regeneration. Young beekeepers warn that pesticides, temperature shifts, and deforestation endanger these keystone species. - Cultural and spiritual losses

Disrupted agricultural calendars, vanishing medicinal plants, and forced displacement are breaking cultural continuity. Women leaders speak of losing crafts, ancestral cooking, and herbal medicine—losses that cannot be measured in economic terms but are essential to collective well-being. - Agricultural decline and food insecurity

Extreme weather, soil degradation, and plagues reduce yields of staples like maize, cassava, beans, plantain, and sesame. This undermines food security, particularly for women and children, and erodes seed sovereignty.