Essex Human Rights Centre Clinic produced a research report on debt justice, corporate capture and human rights, in partnership with ESCR-Net

Particularly for low- and middle-income countries, the financial, public health and environmental crises of our times constrain governments’ ability to respond to the immediate and essential needs of their people. This phenomenon has heightened inequality, imperilled human rights and deepened impoverishment.

In the face of the polycrisis of our times, civil society organisations, academics and activists from all over the world are calling for a human rights and transitional-justice based approach towards debt justice and climate justice.

The modern international debt architecture is based on the influence of neoliberal economic policies, which prioritize private actors and profit over people and the planet. Initially, sovereign debt was used by colonising nations as a tool to secure capital for the building and maintenance of their colonial empires. Over time, Western states and institutions have developed the sovereign debt model into the multitrillion, multinational and multicurrency network of debt instruments that we see today.

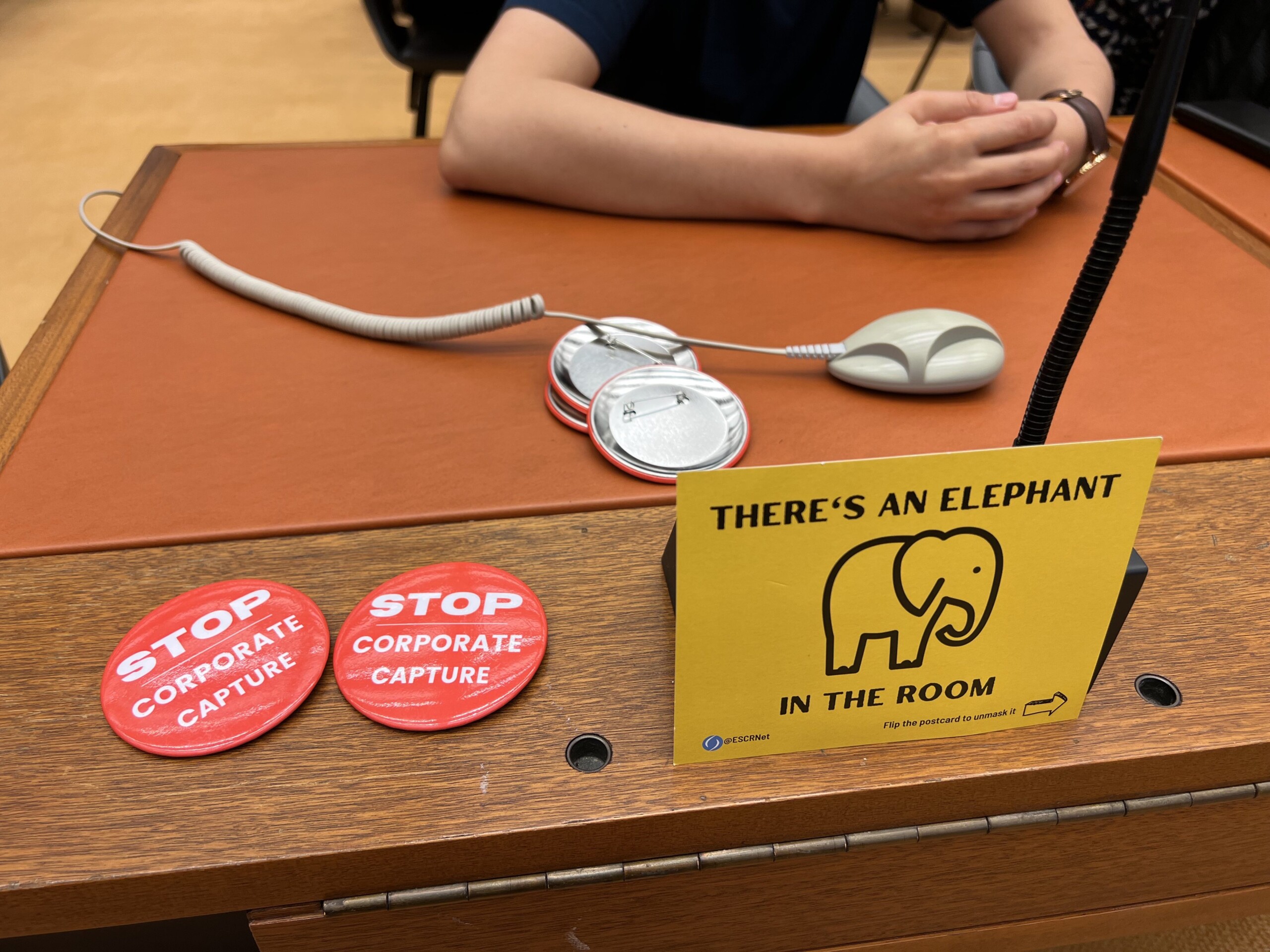

This system has been created by and for powerful governments, elite corporations, investment banks, and wealthy individuals who have become increasingly involved in the economic, social, and political policies of indebted states. These actors continue to exploit and benefit from the developmental needs of low- and middle-income countries, while unsustainable debt burdens constrain the resources available for these states to fulfill their international human rights obligations.

Based on mixed doctrinal and socio-legal methods, our analysis combined desk research and interviews with experts from several countries. Key themes that were addressed are the international human rights framework, the neoliberal debt architecture, corporate capture, austerity measures, colonial legacies of debt, climate, and transitional justice. We focused on three case studies to illustrate the key observations of the study: Chad, Greece, and Zambia.

As a matter of international human rights law, states must make use of the maximum available resources for the progressive realisation of economic, social and cultural rights. They must seek and provide international assistance and cooperation. Excessive debt burdens may unduly restrict states’ resources and general ability to protect and fulfill human rights obligations.

The report focuses on key actors, structures and instruments that underpin the neoliberal international debt architecture. It is important to examine how business interests can unduly influence laws and policies on sovereign debt. Economic actors, such as credit rating agencies, bondholders, banks, large corporations and international financial institutions contribute to and benefit from sovereign debt. Yet, they rarely face any accountability when debt burdens become unsustainable.

In the case of Greece, the financial crisis began with the government owing over €160 billion to foreign lenders, of which the largest lenders were French and German private banks that took advantage of Greece’s entry into the Eurozone. To stop Greece from defaulting on its debt, the International Monetary Fund, European Commission and European Central Bank lent €252 billion to the Greek government between 2010-2015. More than 90% of this amount was used to pay off the original debts and interests owed to the private banks and lenders, which effectively shifted Greece’s private debt into public debt. The bailout prioritized protecting private foreign banks that lent irresponsibly over the human rights of the people of Greece. The economic crisis and lack of available public expenditure due to high servicing payments has increased poverty and inequality, unemployment, and homelessness. This highlights the significant consequences for borrowing states when loans are not adequately assessed for human rights impacts before or during financial assistance.

Many creditors impose conditionalities such as austerity measures and consolidation. Highly indebted states are pressured to prioritize debt repayment over resource allocation for the realization of human rights. The case of Chad illustrates the negative impact of sovereign debt and austerity measures on the realization of human rights. The country’s debt was taken on without adequate debt sustainability assessments, including human rights impacts. To avoid defaulting, the government adopted strict austerity measures that have had especially retrogressive effects in the health and education sectors. For example, from 2013-2017, public health spending was cut by over 50% and primary and secondary education expenditure was cut by 22%. These retrogressive measures meant that many people would wait until their situations were dire before seeking expensive healthcare services, and the rates of school dropouts increased, especially among young girls, who face gender-specific barriers to education.

It is necessary to address the relationship between climate and debt. Although climate change is a global issue with global consequences, developing countries in the Global South suffer the most severe impacts despite having the least historic carbon emissions. Climate-vulnerable countries spend more money on fulfilling their debt repayment obligations than investing in climate mitigation and adaptation measures. In the case of Zambia, the projected debt servicing budget in both 2021 ($1.55 billion) and 2022 ($2.27 billion) exceeded the $1.45 billion allocated for climate adaptation. In 2021, the government did not allocate sufficient resources to tackle the acute food insecurity that affected 1.18 million people, following climate events such as prolonged droughts, floods, and locust swarms. A 2018 study demonstrated that between 2007-2016, borrowing by climate-vulnerable countries cost $62 billion more in external interest payments, and this is projected to increase to between $146-168 billion between 2019- 2028. Between 2015-2022, 55% of Zambia’s climate change adaptation funding was in the form of loans rather than grants, which further increases the country’s debt burdens even as it is in the process of debt restructuring under the Common Framework.

A transitional justice-based approach can contribute to addressing the root causes of high debt, the inequalities in the causation of global warming, and the link between sovereign debt and climate justice. Utilizing the pillars of truth, justice, reparations, and guarantees of non-recurrence may contribute to transitioning towards a debt and climate-just global economy.

Key recommendations and calls to action for both private actors and states include:

- International Financial Institutions and regional development banks should ensure that human rights impact assessments are conducted before, during, and after the implementation of financial assistance programs.

- Lenders and creditors should incorporate human rights obligations into debt sustainability analyses to ensure that debt servicing does not amount to impermissible retrogression in terms of the realization of economic, social and cultural rights.

- Human rights impact assessments and sustainability analyses, as well as lender negotiations, terms, and conditionalities, should be made public.

- Global North states should pay the climate debt owed to climate-vulnerable Global South states through grant-based climate financing rather than loans, which contribute to high debt burdens.

- Debt restructuring mechanisms, such as the Common Framework, should be reformed to mandate the participation of private sector creditors.

- Debt- and climate-vulnerable countries should prioritize allocating resources to tackle the adverse effects of climate events over debt servicing, which fulfills the economic interests of creditors.

- In cases where debt servicing results in impermissible retrogressive effects to economic, social and cultural rights, lenders and creditors should urgently renegotiate the terms and structure of the debt. This may include pausing debt payments, changing interest rates, or reducing/canceling the sovereign debt in order to prioritize states’ human rights obligations.

The research was conducted by Dakota Anton (LLM International Human Rights and Economic Law candidate), Malaika Nduko (LLM International Human Rights Law candidate) and Adeyinka Olaleye (LLM International Human Rights Law candidate), under the supervision of Dr Koldo Casla (Essex Law School Lecturer and Director of the Human Rights Centre Clinic).