Summary

Anil Kumar Mahajan joined the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) in 1977, starting a career in which he was subjected to multiple suspensions and, ultimate, forcible retirement in connection with a mental health disability. He was placed under suspension from February 17-24, 1988. From February 24, 1988 until February 24, 1990, he was suspended a second time. He was placed under a third suspension on May 20, 1993, subjected to official inquiries, and ordered to appear before a Medical Board. Among the charges against him were that he had “become a victim of imbalanced mental illness,” and that he was “unstable and mentally sick.” After many years of suspensions and administrative proceedings, Mr. Mahajan sought voluntary retirement on February 25, 2000. His request was rejected on April 29, 2002, on the grounds that he was not eligible for voluntary retirement because he had not served the minimum requirement of 20 years of service. On December 4, 2004, after 11 years of pending investigation, an Inquiry Officer submitted an ex-parte report against Mr. Mahajan, finding him “completely insane.” On October 15, 2007, while further proceedings related to Mr. Mahajan’s case were ongoing, Mr. Mahajan was compulsorily retired from service.

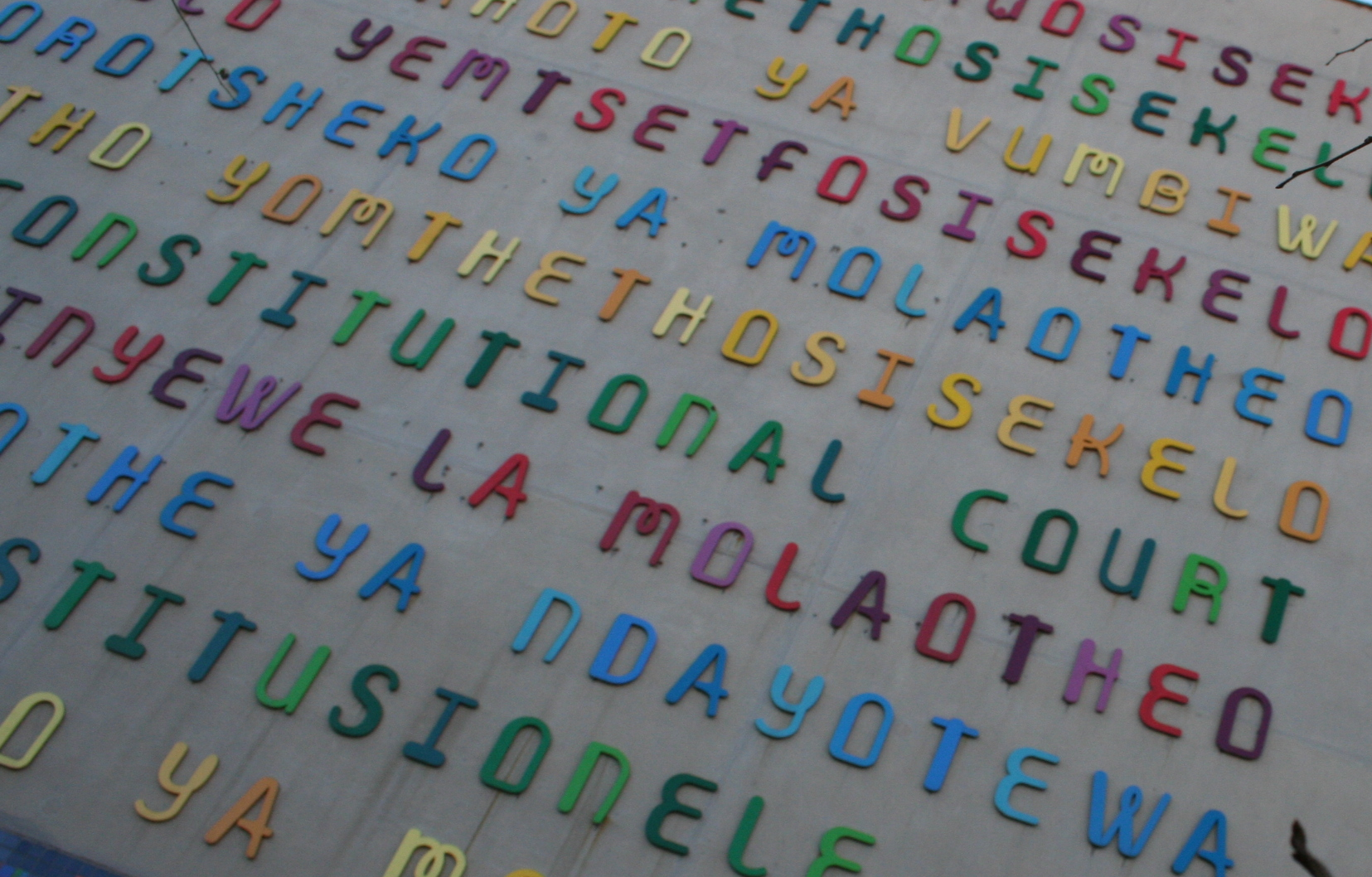

In reviewing the long record of Mr. Mahajan’s case, the Supreme Court highlighted relevant portions of the Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act of 1995, which includes a prohibition on dispensing with or reducing in rank, “an employee who acquires a disability during his service.”

The Court found that Mr. Mahajan was appointed as an officer of the IAS in 1977, and that he had served for 30 years until his compulsory retirement in 2007. The Court found that Mr. Mahajan did not have a mental disability when he was appointed as an officer, and so there was a presumption that even if he developed one after entering the IAS, he was protected under the Persons with Disabilities Act from dismissal or reduction in rank. Pursuant to the Act, if Mr. Mahajan was no longer suited to the responsibilities of his position as a result of mental illness, the Court found that he should have been moved to a different position with the same pay and benefits, or if there was no suitable position, kept on a supernumerary post until he reached retirement age. The Court concluded that the respondents did not have the option of dismissing or forcibly retiring Mr. Mahajan.