ESCR-Net members affirm support for Common Charter for Collective Struggle

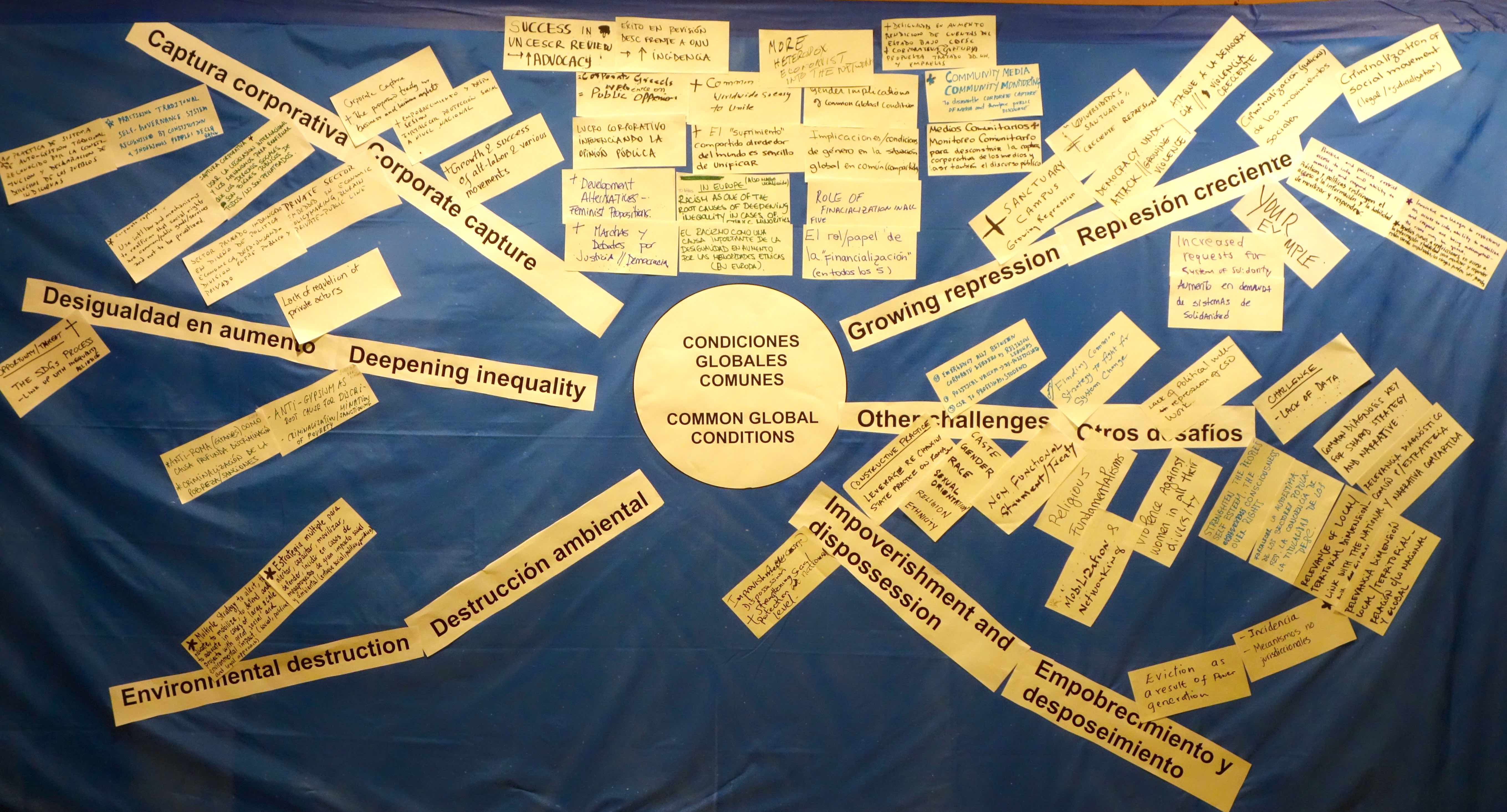

During the concluding address to the Global Strategy Meeting presented by representatives of ESCR-Net’s Social Movement Working Group (SMWG), over 140 hands raised in the air, affirming the Common Charter for Collective Struggle (Charter) as a basis for shared analysis and guide for collective work for the coming period. The Charter was conceived as a framework for a collective conversation about how to address the common conditions pushing communities into struggle: impoverishment and dispossession amid abundance, corporate capture of the state, deepening inequality, degradation of ecosystems and climate change and growing repression. In the months leading up to the meeting, members of each of ESCR-Net’s thematic working groups contributed feedback and additional points to strengthen the text. This revised Charter was presented and then further discussed in small groups on the second day of the Global Strategy Meeting, before being endorsed by ESCR-Net members in the final session.

Common global conditions and shared challenges

The Charter begins with a discussion of some trends that characterize the economic, political and social context in which ESCR-Net members are working to advance and promote human rights. These include impoverishment and dispossession amid abundance, resulting a widening wealth gap that has grown more pronounced due to economic-political practices that, despite the existence of sufficient global resources able to ensure human wellbeing, concentrates the resources and productive capacity into fewer and fewer hands. ESCR-Net members rejected the suggestion that poverty is an inevitable byproduct of a global economy, decrying the commodification of people and nature, livelihoods dispossession, the marginalization of women and criminalization of the poor. Participants underscored their resolve to counter corporate capture of government institutions, and to confront a corporate-police state, which is, according to Melona Daclan Repunte of Defend Job, Philippines “increasingly willing to use police and military to serve the interests of capital instead of people.”

Members noted that, historically, deepening inequality has often been justified and maintained by gender stereotypes, racism and discrimination against minority groups, as well as other forms of fear and prejudice. It was noted that histories of oppression, often integrated with exploitation and dispossession, mean that women and certain groups are disproportionately excluded and impoverished. These inequalities are further exacerbated by climate change, as well as other forms of both deliberate and negligent degradation ofecosystems such as forests, rivers and oceans. These conditions impact most severely on the world’s poorest people, whose immediate survival is often dependent on such ecosystems, and are often based in areas far from the sources of the original carbon emissions.

Human rights defenders working to advance economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR) also face intensifying repression which has, according to the Charter, been bolstered by a wider politics instigating fear and prejudice which characterize human rights defenders as criminal, anti-national, extremist and otherwise illegitimate. In response, the Charter calls on ESCR advocates and social movements to collectively confront the root causes that have prompted social movements to mobilize in the first place to defend or promote ESCR, after necessary solidarity actions are taken.

Since its founding, ESCR-Net has consistently been guided by some core principles, including a commitment to ensuring regional diversity, the centrality of grassroots groups and social movements, and gender balance in leadership and intersectional analysis. The Network has also explicitly sought to ground its activities in the lived experience of people affected by ESCR violations, as well as in advancing concrete, collective actions able to affect systemic change. The Charter is clear illustration of the Network’s commitments to these principles.

As a document initiated by the SMWG and circulated among regionally diverse members for their inputs, the Charter also calls attention to the disproportional impacts of the above-mentioned conditions on women and members of certain groups. Key economic, political and cultural trends have pushed women, in particular, into vulnerable situations of employment; exacerbated women’s exclusion from ownership over land, financing and other productive resources; compromised their access to essential services, such as health care and education; and rendered their economic contributions invisible. Similarly, the Charter acknowledges the historic oppression and exploitation experienced by indigenous people, Afro-descendent communities, persons with disabilities, people pertaining to lower castes, LGBTI people, migrants and refugees, among others. In endorsing the Charter, members underscored their commitment to promoting substantive equality for women and other marginalized groups and attention to an intersectional analysis in all areas of ESCR-Net’s work.

Emerging Points of Unity

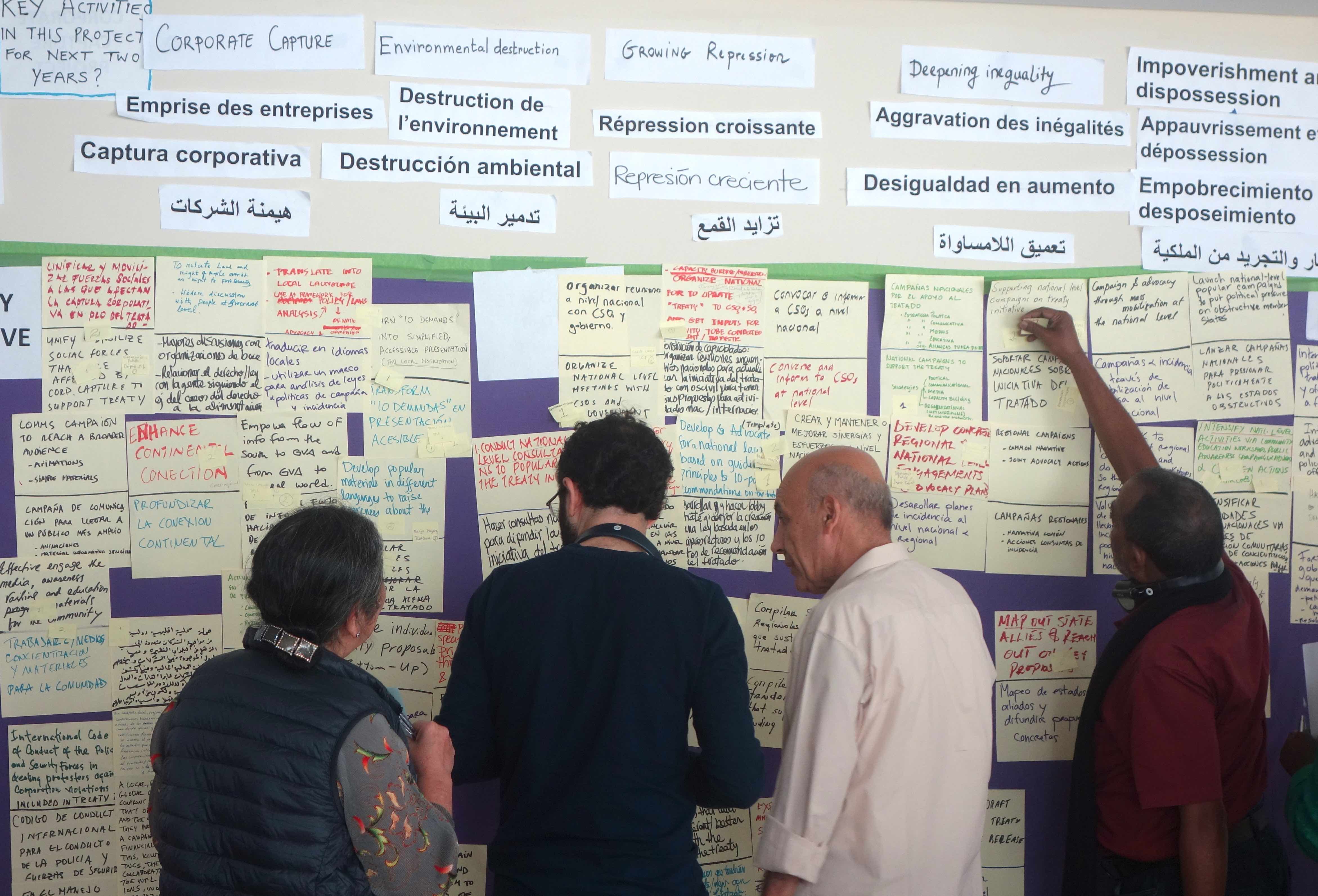

Building on the shared analysis of global conditions, the Common Charter for Collective Action also articulates emerging points of unity which serve to connect struggles and envisions the potential of greater collective action and network-wide campaigning, based on the principles and convictions that unite the various struggles, and activities, of ESCR-Net members.

These begin with the shared effort to reclaim human rights. According to Larry Cox from the Kairos Center for Religions, Race and Social Justice, this requires that we “remember the source of their power... history is clear that governments took human rights seriously only when they were forced to do so by the movement of people fighting for those rights. It was the truly global struggle of people from all countries that has given those rights their power.”

In order to confront the injustices that characterize the landscape for human rights action today, the Charter calls for grassroots leaders and advocates to deepen connections between their struggles and begin to understand these as part of a global movement united to confront injustice, inequalities, dispossession and exploitation. Such a movement would, among other things, confront the disproportional power of corporations and their ability to exert undue influence over democratic processes. It would call on the governments of the world to recognize that food, housing, health care, education, social security and others must necessarily be understood as rights, with corresponding and legally binding obligations, and not merely as aspirational “goals.”

A global movement comprised of articulated actions for social justice would also, argues the Charter, question the predominant drive for profit over the wellbeing for the great majority, amid deepening inequality and the critical threats to human dignity that are posed by the poverty in which millions of people are compelled to live. Rather than understanding poor people as victims of an unjust system, the Charter calls for a commitment to advance the leadership of the poor and marginalized in effecting positive social change, based on their lived experiences.

The Charter clearly identifies those forces and trends which must be countered; as Ida LeBlanc of the National Union of Domestic Employees of Trinidad and Tobago said, “ESCR-Net’s social movements are all calling for the same thing: to end poverty and violence against the poor and those that fight to defend their rights.” Yet, it also indicates a way forward: a call for articulating and amplifying alternative models which affirm human dignity, demand substantive equality for all, safeguard the right to claim rights and envision a common future. In the words of Herman Kumara from the National Fisheries Solidarity Organization of Sri Lanka “another world is possible, and necessary, and we are the vehicle to get there.”

Following the concluding address by social movement representatives, ESCR-Net members registered their agreement with the Charter as a guiding document to inform collective work moving forward. In doing so, participants also committed to the difficult work of identifying points of connection between diverse struggles and deepening an analysis of systemic conditions facing many communities, as initiated by the SMWG. Furthermore, this included a commitment to establish a process to develop coordinated collective actions, and possibly also a campaign, which respond to the urgency of the moment and draw on the strength of the network’s collective voice.

In connecting these struggles, a coherent plan for coordinated action, perhaps in the form of a global campaign, would reveal not only the contradictions of the current economy and related political systems and elevate transformative alternatives, but also build the analysis and broader leadership necessary for “a global movement to make human rights and social justice a reality for all.”